-

Sachin S Jaltare, Untitled

Sachin S Jaltare, Untitled -

Sachin S Jaltare, Untitled

Sachin S Jaltare, Untitled -

Sachin S Jaltare, Untitled

Sachin S Jaltare, Untitled -

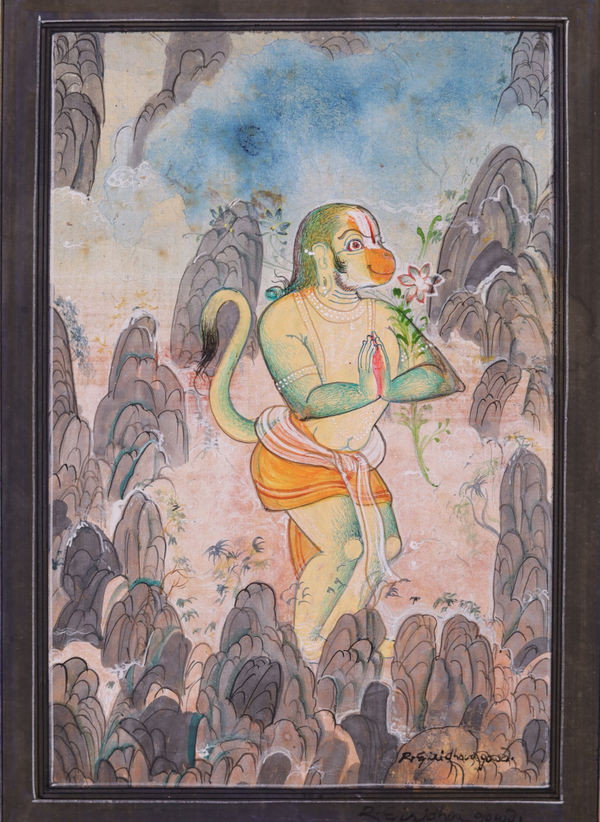

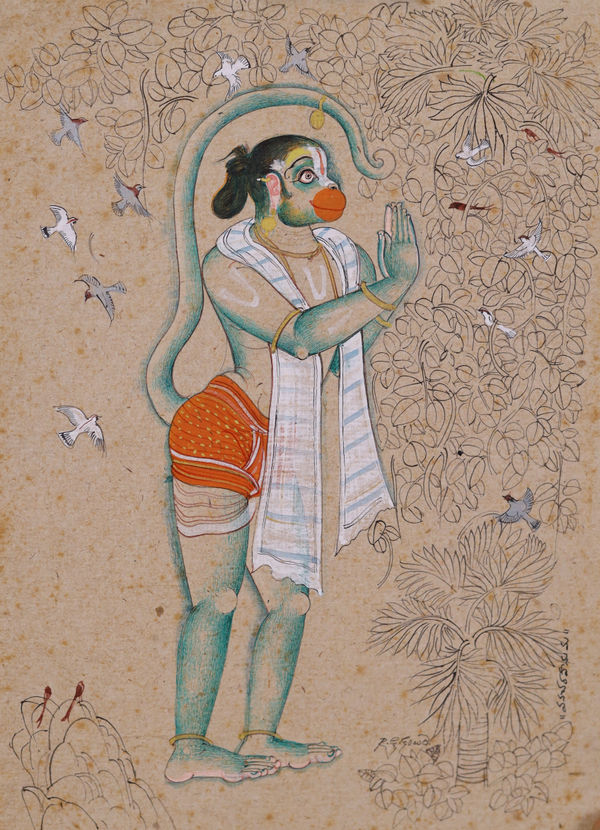

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Chudamani Sangraha Hanuman

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Chudamani Sangraha Hanuman

-

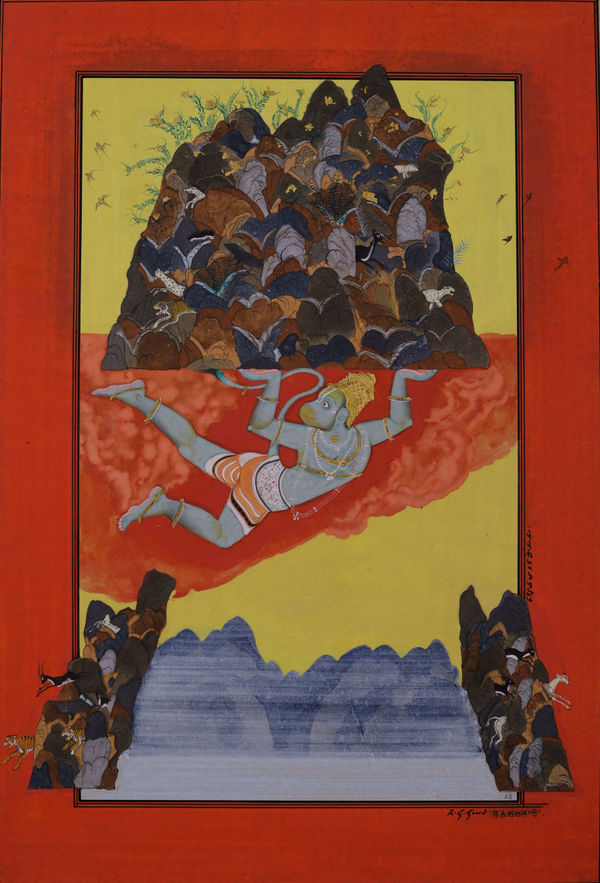

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Parvatabharaka Hanuman

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Parvatabharaka Hanuman -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Aiswarya Srirama

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Aiswarya Srirama -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Bibhasta rasa-Parasu Ramavatar

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Bibhasta rasa-Parasu Ramavatar -

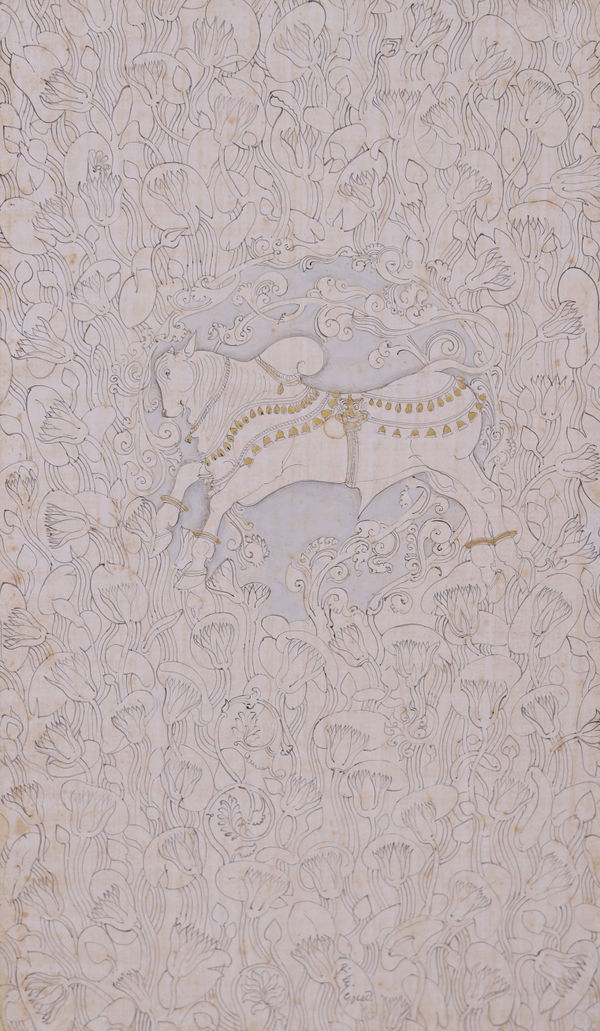

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Bull in Lotus Pond

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Bull in Lotus Pond

-

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Chandra Sahodari Mahalakshmi

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Chandra Sahodari Mahalakshmi -

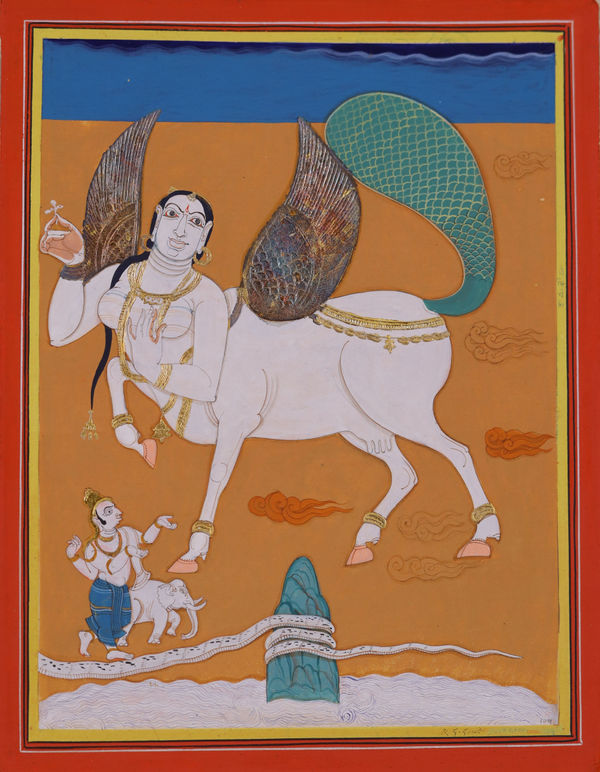

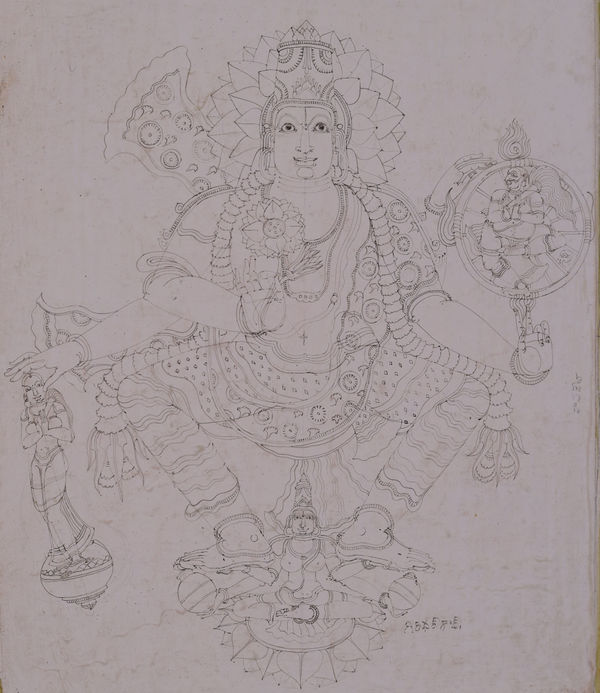

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Garuda

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Garuda -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Greeshma Ganapathi

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Greeshma Ganapathi -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Haasya rasa-Vamananavatara

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Haasya rasa-Vamananavatara

-

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Hanuman Vahana Srirama

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Hanuman Vahana Srirama -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Kamadhenu

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Kamadhenu -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Kammadhenu

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Kammadhenu -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Adbhutaa rasa-Varahavatar

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Adbhutaa rasa-Varahavatar

-

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Kinnerulu

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Kinnerulu -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Kishkindamalla Yuudham

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Kishkindamalla Yuudham -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Mahalakshmi

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Mahalakshmi -

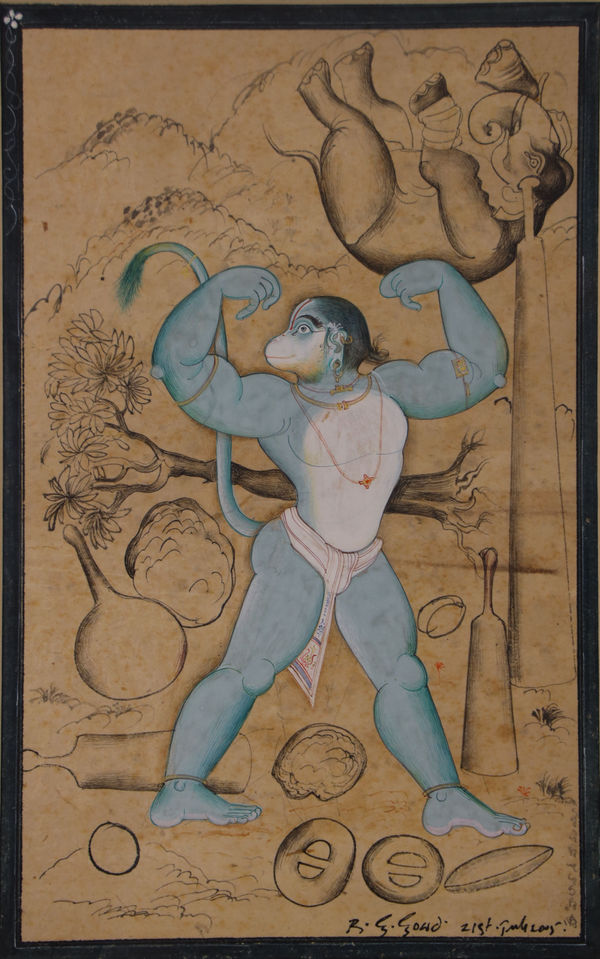

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Malla Yodha Hanuman

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Malla Yodha Hanuman

-

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Mastyavatara

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Mastyavatara -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Panchamukha Hanuman

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Panchamukha Hanuman -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Saavadhana Chitta Hanuman

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Saavadhana Chitta Hanuman -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Samudra Langhana Hanuman

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Samudra Langhana Hanuman

-

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Sanjeevani Sangraha Hanuman

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Sanjeevani Sangraha Hanuman -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Sanjeevani Sangraha Hanuman-I

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Sanjeevani Sangraha Hanuman-I -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Sanjeevani Sangraha Hanuman-II

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Sanjeevani Sangraha Hanuman-II -

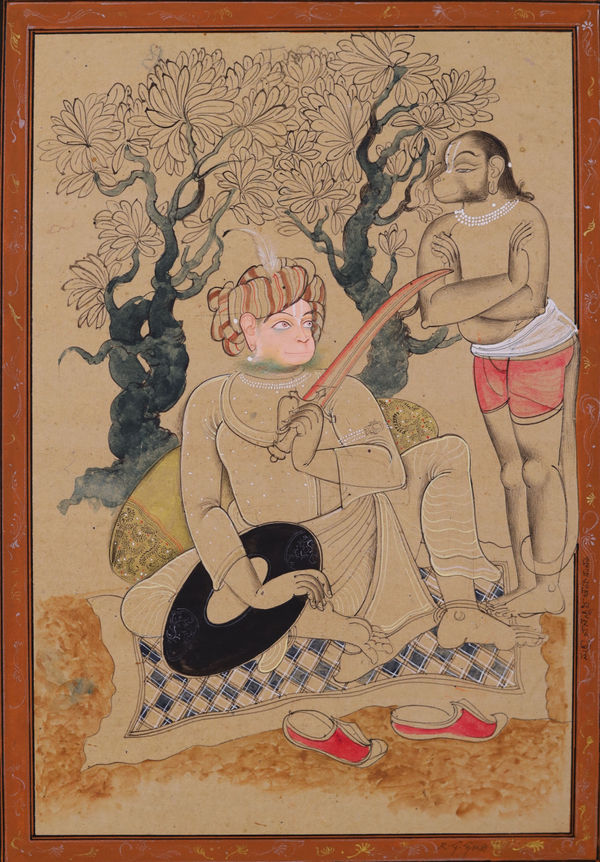

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Shanta rasa-Buddhavatar

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Shanta rasa-Buddhavatar

-

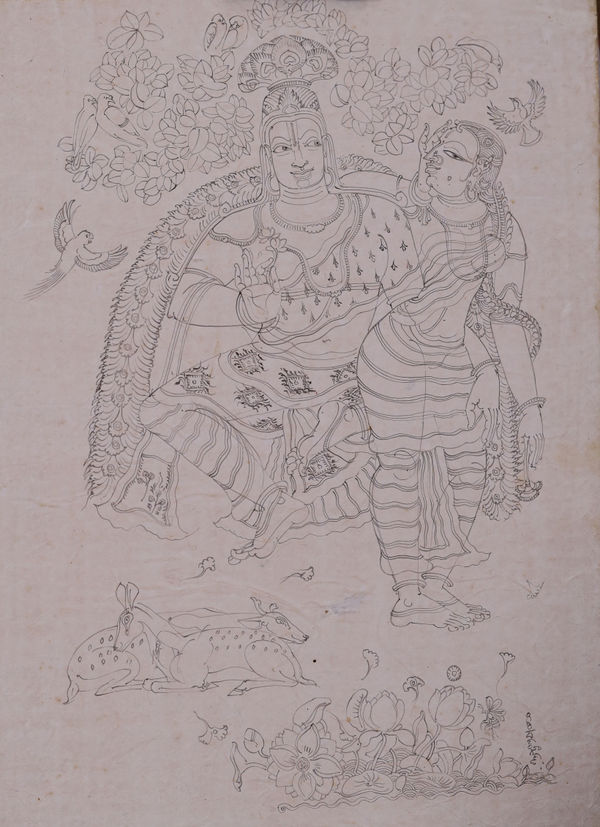

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Shringara rasa-Sri Krishna

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Shringara rasa-Sri Krishna -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Sila Vandita Hanuman

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Sila Vandita Hanuman -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Siva Dhanurbhamgam

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Siva Dhanurbhamgam -

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Sugreeva Sannihitha Hanuman

Rayana Giridhara Gowd, Sugreeva Sannihitha Hanuman

EXCAVATING CUTUAL TRADITIONS: VERBAL TO VISUAL

Giridhara Gowd is a nationally acclaimed and well known established artist, a name to be reckoned with, when it comes to contemporarizing mythical epic stories with his individualized, vision, imagination and sensibility. Earlier he had worked on the Dasavatar and Krishna Leela series. A flaneur of sort, desiring in finding sensuous pleasure in the narrative, the inherent philosophy that is subtly laced and cloaked in various stories in the epics, but above all it is the cultural roots of tradition manifest in the epic narratives, in the visual aesthetic of India’s pictorial tradition and the varied regional and folk styles visible in the murals at Lepakshi, Badami, Aihole, Hampi, Pattadakkal, Tadipatri, Srisailam, Kalahasti, Tirupati, and especially the paintings in Vijayanagara called Bhitti paintings that attracts and inspires Giridhara in its multitudinous dimensions and characters to produce works marked with subtle sophistication, originality and creativity.

Giridhara Gowd is an artist based out of Garuvupalem, a small rural village in Guntur District of Andhra Pradesh. His methodology in terms of technique and format, thematic content and subject matter mark a return to tradition in its redefinition, infusing with renewed vigour, vitalized vision and reinvention. At the heart of his creative endeavour is his engagement with country’s visual art tradition particularly the murals and miniature paintings. He foregrounds these pictorial arts to serve as conduit of creative expression, thinking and articulating through epics, Puranic and mythical narratives. Giridhara says, “I have developed an immense interest in stories, poems and historical legends from my childhood. I have always approached these legends not as religious, superstitious stories but as priceless epics, a treasure house of wisdom and as unique examples of the essence of life”. It is in the winnowing of narratives, through a figurative visual language, which allows him to interpret according to his experiences, perceptions and most vitally his inner most desire to bring forth with a new vocabulary the translation of the verbal into the visual through his meaningful comprehension of this episteme premised on his imagination. As a matter of fact the latter plays a seminal role in decoding the semiotics of the epics and stories to provide the semantic on his terms but knowledgably.

With a mindset that is anchored in experimenting and exploring the miniature and mural traditions juxtaposed with retelling and reimaging the epic stories, Giridhara has taken absolute delight in representing it as a deft stage director in a well thought out, intelligent, simplified yet meaningful, and structured manner. It is through the vibrant visual aesthetics, in which the element of line becomes the primary protagonist in defining and communicating his ideas while the colours enhance the potential of the narrative. Giridhara has capitalized on important leading characters from the Ramayana epic, derived from Valmiki Ramayana’s Telugu translation by Professor Pullela Ramachandrudu, a Sanskrit Pandit, Telugu translator and scholar. He has articulated varied expressions, premised on the episteme of the rasas and bhavas as well as the meaning of significant life inherent within these stories. Through the principal protagonists Rama and Hanuman, Giridhara, in the present suite of works, not only reclaims the implication and seminality of these important dimension of Vaishnavism but pictorially it remains his attempt to foreground India’s ‘desi’ or folk and tribal and classical painting traditions. It is this dimension of the present suite of works which makes it significant, since his objective is to explore and experiment with the techniques, mediums and materials of miniature and mural traditions, through the stories of Ramayana that essentially serves in providing the subject and themes for his works. It becomes dialectical, as the medium and technique changes to transform to suit the contingent moments in the development of his visual language and vocabulary, that is, either miniature or folk art. It is his attempt to maintain the traditions alive of varied aspects of Indian culture within the collective sub conscious. To realize his aims of verity he has gone to the extent of sourcing from classic text as Vishnudharmottara the idea of representing clouds and other elements of the Panch bhutas.

Giridhara’s primary objective through the two protagonists is to reflect on life, the capacity of the human soul to transcend many levels of struggles, desires and wants to reach the ultimate union with the Supreme Being. Considering human body as a step ladder, he attempts to establish the possibility of slowly raising the ‘self’ to transcend to ‘higher self’. In addition to this he also has played upon the bhavas or the emotions of various characters to establish the Navarasa or the subtle flavours of appreciation through the medium of Dasavatara of Vishnu representing the avatar as a rasa as the adbhuta in Varaha avatar for instance. His engagement with the textual traditions of the country including the iconography and symbology, as well as well as the sculptural heritage witnessed in the historical temples were dynamically reinvented, re-imagined and redefined according to his contemporary sensibility. It is in these interpretation and articulation that the originality of Giridhara is invested and which allows him to mark a posture of difference.

In this new suite of works, Giridhara has not only given iconic representation of Rama, Lakshmana, Sita, Hanuman and the kingdom of Sugriva, but has astutely engaged with different visual styles as manifest in mural and miniature tradition of the country. Obviously noticeable is the Lepakshi mural tradition, the glass paintings of Tanjore in the use of gold leaf and Surpura miniature paintings in Karnataka. The latter paintings are believed to have gained popularity in the region when a group of migrant painters following the disintegration of the Vijayanagara Empire after the Battle of Talikota in 1565 settled here. The painting style bears strong similarities to Mysore and Tanjore style including the use of gesso, bright colours, and embellishments such as gold leaf and semi-precious stones. Most Surpura paintings depict Hindu religious and mythological figures, with a focus on Vaishnava subjects. Giridhara’s interest in the Surpura miniature tradition was ably aided and facilitated by his first guru Vijaya Hagara Gundige of Gulbarga who is a miniature painter of the Surpura tradition. Yet moving beyond these influences, it is seminally important to mention that eminent Baroda artist, pedagogue, author and storyteller Gulam Mohammed Sheikh had equally been instrumental in providing the thrust to paint in miniature format. But for Giridhara an overwhelming inspiration and teacher was the artist and collector Jagdish Mittal of Hyderabad, who carries the equal gravitas in driving Giridhara’s passion for creating painting in miniature format. In addition to these seminal artists who were instructive in the artist gaining knowledge about miniature traditions, there were a few more teachers who extended his experience in miniature tradition as Uma Shankar Sharma, Devaki Nandan Sharma of Bhnstali Vidya Peet from the ateliers of Udaipur and Nathadwara in Rajasthan.

A CRITICAL GLANCE AT GIRIDHARA’S PAINTINGS

In the analysis of a work of art, it mandates the mentioning of the technical process engaged to by the artist for a better aesthetic comprehension of his art. This holds true for Giridhara who assiduously followed the traditional methods to obtain the desired results. As a contemporary artist he has brought in changes in the medium dependent on the subject he chooses to paint. This relates to the type of paper, the natural colours, binding medium, and the tools he has utilized.

Paper the most vital element in art as a support for the artist, has been carefully selected by Giridhara to establish his creative expressions. He has primarily made us of the handmade paper as the Wasli, Bamboo pulp paper, silk paper, Bhutani paper, Rice paper, Sanganeri, which are some of the traditional supports that he has worked with. In order to get the required thickness he layers many papers together on acid free mount board. Sometimes the paper itself is layered. The surface of the paper is then prepared by coating it with fine coats of Khadia-white chalk which is mixed with the gum Arabic. After the coat is dry, he places the paper upside down on a glass and burnishes with Akeek a fine polished stone to make the surface smooth. The paper is now ready to receive the drawing, which is executed with very fine lines. Over this, layers of colours in thin washes are applied according to the subject and the thematic content. After every layer of paint has been applied, the painting is burnished from the back with Akeek stone. When the last fine details are added, Giridhara adds gesso to the pigments in order to render the delicate ornaments. The work is finally finished with the gold leaf applied in designated parts with the gum, and the final finish is with the fine lines to give it an aura of finality. In order to create the glitter in gold, it is burnished to enhance the effect.

The colours in his works that give the effect of brilliance and freshness are derived from minerals as red from Hinglu, brown from Geru and laal mitti, yellow from Haldi and Gambose, green from Terrawart and Indigo leaf, blue from Indigo vegetable colour, black and grey from lamp black charcoal and sonar sone, pink from peepal ki lac, orange from Ganga Sindhoor and white from lead white, chalk and zinc white and khadi.

The tools are also traditional making use of squirrel hair brushes as well as fine quality synthetic brushes that are commercially available. Hence materials and tools are instrumental in creating the desired effects and finish that Giridhara requires and remains the rich bed rock of his methodology in visualizing the narrative content.

In critically appreciating his works, it is the rich and prolific imagination that is striking. His pictorial semiotics carries special meaning. By making it a trope or giving it a twist, Giridhara’s works demand that his protagonists be construed not literally but metaphorically, which is reinforced by his choice of subject matter as evident in the examples cited below. An analysis of Giridhara paintings whether miniatures or acrylics on canvas, the narrative that captures the imagination is his insightful engagement and articulation with his elements namely line, colour, space and texture. Extending further, he crucially redefines the iconography that is in consonance with his imagination and philosophical concerns. For instance the “Airvatham Jala Kreeda”, is a drawing on gesso in a circular compositional format, which is an endearing representation of the elephant or the vahana of Indra, frolicking happily and joyously in the waters. He is surrounded by the lotus leaves and flowers, with fishes, cranes, bulls and dragonflies completing the ambience. In many respect it is possible to interpret Giridhara’s arbitration with certain flora and fauna as well as the icons from the Ramayana as his ‘other’, which as explained in the psychology of the mind by R.D. Laing is that which identifies and refers to the unconscious mind, to silence and to language or what is unsaid; it also indexes towards the questions of identity, consciousness, empathy, and social interaction. Perhaps many unsaid complexities that the artist harbours and which cannot be expressed openly finds a covert representation through ‘the other’. This could be estimated to his predilection for delight, passion, compassion, empathy, love, relationship and the varied emotions brought to the fore with absolute energy and dynamism. His paintings deny any form of stillness in its artistic expressions, rather pervading verve and vibrancy that embodies all his works. It is this energy of emotions, movement, postures, gestures and glances, which is at the heart of his works and establishes the peculiar saliency that becomes his signature style.

In the miniature format of his drawings on paper primed with gesso, particularly exhilarating are his depiction of Navarasa that is delineated imaginatively, sensitively and in a synoptic manner. The rasa or the aesthetic sentiment is established through his fluency of line, draftsmanship, dexterity and skill of the art and craft of drawing. In its ascetic austereness complimented with his fecund imagination, the Navarasa establishes the rhythm of his creativity, implicating the Dasavatar of Vishnu through the medium of Rasa. For instance the “Srinagara Rasa” has an unusual representation of Krishna and Radha, involved in subtle romantic theatrics through the glance of the Krishna admiring her through the corner of his eyes, while Radha’s glance is turned away from him in light poetic and shy manner. But Krishna holds her firmly, with a feel of light breeze tenderly touching her as he is seated and she stands next to him, charming and beautiful with her arm tenderly resting on his shoulder. Giridhara images the romantic involvement as a dancer would attempt to convey with elegance and aesthetic rhythm of her body. The romance does not end here, Giridhara conveys the rasa of love in Prakriti as he delineates the deer couple with romantic intimacy, the lotuses in the water ripple with rhythmic dancing grace as each touches the other and moves away, creating the enigma of drama of love while the birds in the foliage are rendered as couples lost in the warmth of each other. The visual aesthetic of this drawing is as interesting as it is synoptic in its representation. The rasas which has been delineated with sensitivity and warmth of compassion is “Karuna rasa” and the other with fantasy and fecund versatility of imagination is the “Adbhuta rasa”. The former is soul inspiring and touching as Rama warmly and lovingly holds Jatayu in his arms with his head resting on the bird. Jatayu is in pain and ruthlessly injured with its wing partially cut off and lying next to him, while his head is encircled in the arms of Rama, carries the expression that will tug the heart strings in its emotion of pain, loss and empathy for Jatayu, while the latter finds solace in Rama’s tender hug. Giridhara reveals himself as a perfect director in choreographing the range of emotions. The sobriety and somber ambiance is further enhanced by a single lone cloud shedding tears on the tragic scene below. In the “Adbhuta Rasa” Giridhara’s imagination has taken flight in delineating the Varaha Avatar of Vishnu. In its compositional format, he has divided the elements of the narrative representing the Varaha in an energetic and dynamic posture as he lifts the mother earth out of the abyss of the ocean. But the only difference here is that Varaha does not carry her on his shoulder as is the traditional iconographic representation, but the artist has given it a trope by providing multidimensionality to mother earth by showing the entire Prakriti of the world of flora and fauna while she sits majestically in the centre with her four arms holding the kalasa symbolizing her saliency of nurture and care. The lines in this composition are not only descriptive and narrative, but are laden with inherent potential energy, as the Varaha Vishnu in his triumphant moment has the dynamism to perform any task. The energy radiates with verve and vigour that is unstoppable.

Giridhara works could be categorized as pluralistic, that is as a refinement or repetition of preceding styles, reworking old grounds as the mural and miniature traditions in its technique, aesthetics as well the subject matter. Perhaps within postmodern philosophy a return to mural and miniature tradition can be read as an exaggeration and a response to the artist’s need and demand for innovation, which he fulfills by bringing a rearrangement of iconography, without losing its original context. For instance in “Kamadhenu” the artist has given the representation of the cow sans the woman’s head but maintaining the wings, flying through the clouds, with the rippling river below. It is these individualized and sensitive innovations that he was able to cut through tradition to create his own icons and establish his voice.

Hence the argument thus establishes creativity and artistic advancement as necessarily connected to having new ideas about what counts as the essence of art. This then can takes on a new form or style of handling or refinement of an existing style, which is well demonstrated by Giridhara in nearly all his works to an optimum degree. It nevertheless is the pattern and structure of these sorts of developments, which are the key elements in the history of art. In the words of Emile Nolde, “Without much intention, knowledge or thought, I have followed an irresistible desire to represent profound spirituality, religion and tenderness.” Extended to Giridhara, the concept bears significant relevance. His intentions has always been to reinterpret the episteme of epics according to his sensibility and breadth of knowledge, on the basis of which he conceptualized his paintings, which manifest philosophical, spiritual and tender emotions.

The saliency of his paintings bear raw naivety, dynamic energy and a simple spontaneity, arising out of his perceptions of the world, recording the events and natural phenomenon with fluid ease, directness and acute insightfulness. His impulsiveness to travel to various heritage sites as Ajanta, Ellora or any other makes him an itinerarant wanderer of his deep felt subjectivity, recording the phenomenal world in his sketch book which is the ‘other’ or shadow of Giridhara. On his varied travels and rambling jaunts in his rural village, anything that captures his imagination is immediately jotted in his sketch book. It is this volume of vocabulary of objects, things, flora and fauna that gradually finds its presence in his paintings.

This approach to making art; marks his works with devotional piety and intense passion. Yet in this era of technology, virtual and digital reality, Giridhara remains untouched and uninspired to engage with these mediums in order to articulate his subjectivity. His comfort levels are with water colours, acrylics on canvas and traditional miniature techniques, where he enacts the choreography of the dance of tonal hues and value contrasts with dynamic ease. His strokes magically fly to conjure up subject matter that is as varied as music, dance, flora and fauna, the sublime ambience of a rural countryside, or the popular iconic gods. In capturing these different dimensions of the phenomenal world, Giridhara with immense alacrity is successful in getting at the heart of the character of his subject to capture its essence and saliency. This is where he marks a signpost, in making his works significantly distinct though carrying various flavours of pictorial traditions.

The linear movement of the line remains at the heart of his works as it is an element that Giridhara is overwhelmingly passionate about, declaring his strong predilection in its engagement. The firm confident drawing not only lends visual power and character but is effectively controlled. It also became the vehicle for Giridhara to carry the burden of his expressions; poetically swaying, dramatically walking, shying away, aggressively powerful and dominantly versatile, imparting a sense of melodrama. Hence the fleeting, flying, defining, and playfully describing line aids in evoking tender moments. His detailing is adequate and at the same time he provides volume to his forms through selective modelling. The colours remain pleasant and evocative yet establishing its character. His paintings have an aura of playful charm particularly realized in the eye and the lotus bud that is teased by the gentle breeze and the rippling water. Giridhara through his fantasy and imagination weaves his imagined humour.

In this series, it is possible to generally categorize the representation of important protagonists as Rama, Laxmana, Hanuman and Sita. Yet within it the endearing and loveable Ganesha also finds his auspicious presence. The delineation of every character whether in miniature format or on canvas are imbued with emotions manifested through gestures, postures and glances. “Greeshma Ganapathi” is a symbolic visualization of the ritu namely the summer, when the hot sun beats down mercilessly. Ganesha is delineated feeling uncomfortable with the heat, his legs spread out, fanning himself, with the hot sun partially represented above. Giridhara in a traditional representation as one would have it moves beyond the standardized hot sunny landscape to have the lotus pond surrounding Ganesha, balancing imaginatively the sun’s heat and cool waters. These polarities nevertheless are the inherent energies present in the Prakriti which the artist subconsciously puts forth. In a similar vein is the iconic representation of “Garuda”, depicted majestically. As a bird in constant flight, Giridhara has painted the pearl necklace not as a static decorative ornament but rather in consonance with the movement of his flight, the wings spread out, two hands in supplication with third hand holding an umbrella and the fourth having a poorna kalasa,a symbol of prosperity and auspiciousness. The design of the lower garment worn by the Garuda has resonance to Lepakshi mural painting. The face in profile has the emotion of reverence with eyes lost in the worship of his master. It is an energetic painting in the way the drapery swirls and the pearl necklace sways rhythmically in flight.

His innovative and exploratory iconography finds visual embodiment in certain miniatures and canvases. His most stunning work is the “Vishwaroopa” painted on paper. Its complex iconography and symbols is definitely beyond the scope of this textual writing. But the admirable aspect of this painting is the meticulous way in which the small figurines of men, animals and hybrid creatures are painted on the body. The image of Vishnu follows the representation in the iconic shastras, but it is the combination of the varied symbols, attributes and particularly the Panch bhutas that Giridhara has taken the optimum opportunity to represent as desired by him. The colours are employed symbolically to represent the red fire, blue water, the green brown fertile earth and white conventional clouds. Included at the side within the circle are symbols and metaphors that represent the seven stages within the body to reach the ultimate stage of spirituality. These concepts itself are an abstraction, but Giridhara has brought them alive through his imagination and interpretation of the reading of the Ramayana, enabling the philosophy to manifest meaningfully. Enhancing the compositional structure is the way the artist has painted vignettes relating to Swaroopa, each a dynamo of story narration. But the extraordinary element that captures the imagination is the crown or the mukuta that is painted beyond the frame of the enclosing border. It is in these varied pictorial visualization that Giridhara contemporizes his subject and moves beyond traditional representation, thus avoiding the label of a ‘purely’ traditional artist.

The delineation of Hanuman with his captivating devotion and absolute surrender to Rama, Giridhara has captured the emotional essence in a sensitive and with feelings, as each composition, based on certain event in the life of Hanuman explicates it thoughtfully. The artist has made an attempt to lay bare with honesty and truth the saliencies of Hanuman as possessing dexterity, prudence, humility, and a successful warrior. His compositions titled “Panch Mukha Hanuman” has ferocious representations of an eagle, horse, boar and lion, “Chudamani Sangraha Hanuman”, has him sitting atop the tree, with Sita’s chudamani in his palm, explicating a moment of joy in anticipation of finding Sita, “Sajeevani Sangraha Hanuman” interestingly delineates the Sanjeevni carried effortlessly, “Vaala Priya Hanuman” enjoys the moment of triumph as he kisses the tail, which has done the required destruction in Lanka,, “Hanuman Vahana Sri Rama” exhibits the strength, power and absolute attitude of servitude as Hanuman carries Rama on his shoulders. All the compositions have been meticulously planned and executed in terms of its subject, providing emphasis on the protagonist to enhance his centrality. The inspiration from miniatures manifests particularly in the representation of space that does not have an authoritative central focus of looking at the scene, but rather Giridhara has used multiple perspectives to show different aspects of the scenes simultaneously, particularly obvious in his “Sanjeevanai Sangraha”. The resonance to miniature tradition’s depiction of space remains emphatic. Giridhara has absorbed and assimilated these varied dimensions of representational elements as manifest in the miniatures and has evolved compositions that establish the original vision of the artist.

The compositional structure of all his paintings have an iconic representation of the chief protagonist occupying the central space and important elements of the narrative clearly shown to make the identification possible, thus making the visual reading of the paintings to flow smoothly as the water over polished boulders. His underlying compositional strength and disciplined power imparts a sense of authority in the organization of his varied elements. That is, no element or form in his paintings appears to be randomly or serendipitously placed. Hence comingling and integrating his imagery on the conceptual and imaginative strength, the works have a seminal visual solidity and appeal that makes them timeless.

Nature finds an important space, and Giridhara has taken delight in representing different species of trees, flowers, rocks, animals and birds as well as the rippling water and the clouds both as threatening rain clouds and the soft blue ones. His empirical approach marked by insightful perception allows for subtle lacing of humour as evident in the naughty playfulness of the monkeys in their acrobatic postures, their facial expressions resonating to human emotions of sadness, contemplation, anxiety, triumph and happiness. In fact from within the deep layers of his subconscious, the experiences Giridhara has perhaps gone through, finds metaphoric translation through these sacred narratives as appropriate to the contingent moment of creation.

In painting the sacred narratives he has given a trope that is as the example of the fight between the two twins Vali and Sugriva is metaphorical, signifying the semantics of the saliency that is also human related. He has made an attempt to show the different stages of man from youth to maturity to old age, deepening the factor of astute observation that remarkably invests his works. But the crowning element that makes his paintings vibrantly filled with vigour is the energetic line that curves, flows, leaps, serenely saunters along but all along embodying the inherent dynamism of power that makes Giridhara painting a class in itself. This is further enhanced by the postures of the legs and arms, making each work a potential dynamo. Significantly it relates to the attitude of the artist whose creative energies are equally volcanic in their imaginative eruptions. This undeniably arises from the artist’s deep devotion to his art, juxtaposed with his dedication, passion and commitment that enables a realization of his deep seated desires that unfolds through his arbitrated narratives. In many respect as mentioned earlier the saliencies of Rama and Hanuman are manifestations of the artist himself that he has poignantly portrayed. It requires on the part of the viewer to engage with his paintings in an intelligent way, as it is not the superficial representation of these iconic characters, rather it mandates to relate with it by holding a dialogue of deeper meaning vested within it.

The discerning keen sensibility of Giridhara in delving into myths, clarifies his predilection towards narrative, thus retrospecting to tradition to keep alive the sap of philosophy nestling within our culture. The narrative that Giridhara has created by his engagement with myths may bracket him as an artist with a traditional mindset or an approach. But it is important also to realize that in its visualization as a painting, it remains an arduous task, requiring the artist to cull out those aspects of narrative that would provide the punch visually and simultaneously convey a comprehensive understanding of the episode of the myth. Giridhara in both these aspects is a master as a skilled artist and a clever raconteur bringing alive the epic.

DEFINED AND UNDEFINED: THE AMBIGUITOUS REALM OF SACHIN JALTARE

“Art is the language of the soul, a way to communicate the unseen and the unknown” Shivax Chavada

Sachin S. Jaltare is an established artist based in Hyderabad. Born in Akola district of Maharashtra, he obtained his education from Chitrakala Mahavidyalaya in Nagpur. Beginning his career as an illustrator in a commercial firm, he was advised by a well known artist who recognized his innate talent of artistry to concentrate and focus on a career in painting by releasing himself from the job, which he did and very successfully, and the as they say is history. He initiated his forays into the world of painting with a realistic visual language painting birds particularly, since he is also an ornithologist. As he progressed he found realistic representation limiting, desiring to break out of the form and express freely. Hence he was in search of a visual language that would enable him to express his inner most desires of representing subject that are integral dimension of his life, experiences, perceptions and his philosophical episteme with image and imageries that would be different, enabling him to create a new vocabulary for the expression of the same and an identity for himself.

It was in the early years of the first decade of 21st century that he took to reading on spirituality and meditation and found the verbal medium enabling him to discover answers that he was in the quest of. The energy he discovered in meditation and the reading on spirituality opened space for him in the realization of an unknown force as ‘energy’ which he translated through the concept of Shiva-Shakti or Prakriti-Purusha, the eternal, infinite boundless space and energy. These dimensions crucially began to inform his artistic expression that was to radically change the way he would paint. “In Shiva and Shakti, I find the perfect meeting of the form and the formless” says Sachin, which inherently is the duality of life’s existence that he capitalized upon.

The powerful concept of energy, which offers different reading as body and energy, Purusha-Prakriti, Shiva-Shakti, all aspects and manifestations of a transient world in which time play an equally seminal role. That is to say, it is a dimension of life, which is always on the roll on the move and unstoppable while the ‘self’ or the soul, remains unchanged and eternal. If Sachin was reclaiming this philosophy as means of his artistic expressions, it necessitated a change in his articulation with vocabulary and visual language. Hence this required for him to break out of the limitations of firmly defined body structure; and navigate space and time to create the seen and the unseen. The aspect of time in a way therefore becomes an important element as one of constant change, in the understanding of Sachin’s quasi abstract figurative works.

A painter of the quiet reaches of the imagination; it was not the saliency of Sachin’s artistic persona to be simply mimetic in his representation. He had mastered the skills in realism and his restlessness pushed him into exploring the conceptual terrain which he did by looping back to his cultural and philosophical roots through the concept of play of energy and hence of time. This consciousness allows flux of time to place valence on interpreting and examining cultural paradigms leading towards introspection or meditation on philosophical tradition or nature and hence his development and evolving of the concept of navigating and weaving his imagery through ‘Shiva-Shakti’ in a holistic manner. It was not the religious aspect that attracted Sachin, rather the illusive, the undefined the unsaid aspects of the universe as manifest in Indian philosophy. Within this context, he realized it was “time”, which is a dominant centrality that would offer a different perspective in reinvestigating cultural and philosophical traditions, premised on his experiences to find an appropriate voice. The experiences were the result of the process of questioning existence, introspection on ‘self’ and the impermanency of the transient world which is in the process of constant change. Thus through meaningful and powerful investment in the expression of the fragility and universality of ever changing moment of time and space, Sachin establishes his concept artistically through layered process of painting and finally defining certain forms which carries valence for him as the image of Shiva and Shakti or the phallic symbol or the energizing Prakriti through various elements from the world of flora and fauna.

In his quasi figurative abstractions he thus reflects upon the philosophy as earlier mentioned, which is premised on personal and cultural memory. By the latter is meant his articulation of philosophical ideas as self-non self and the concept of Maya. For Sachin, perceptions and empirical experiences about his cultural milieu as well as his love of nature becomes the rich bed rock of visual material, to be harnessed in a language that would have his comfort levels. His premises for artistic argument equally is on the concern that Purusha and Prakriti are the two highest realities of existence and that both are indestructible and eternal finds realization in his quasi abstract and figurative vocabulary. In order to render this abstraction of the conception of the mind, objects mimetic or otherwise have no valence within his philosophical field. Yet he does not divorce from the physical reality to privilege only the mental images as a form of sublimation for his expressions. True to being an artist, he creates from a place of inner stillness; a characteristic that he visibly communicated through his process and technique. His works offer a reading of materiality, spirituality and creativity.

STRUCTURE AND AMORPHOUSNES: A CRITIQUE ANALYZING HIS METHODOLOGY

A glance at Sachin’s oeuvre foregrounds one dominant centrality and that is, his expressions are both structured and amorphous within the same spatial and temporal field. The artist understands change as permanent. Change carries within itself the concept of time, space and memory. The latter can be explained as both space and time which is representative of mental landscape. It is this dimension that gets foregrounded eventually in his attempt to establish through his paintings, which he equally deftly and intelligently found the correspondence of his ideas through the language of abstraction and the technique of layering. It gave him freedom and autonomy to manage and choreograph his imagery and non imagery to suit his sensibility and thinking.

Within this context of his philosophical approach to reality/universality, Sachin’s art expressions are communicated through the elements of line, colour, textures, light and space. These elements made it possible for the transference of ideas as thoughts and images as his expressions in delineating the realm of energy or in other words as Shiva-Shakti. His element of line that translates as the chief protagonist, carrying the burden of his emotions and cultural philosophy is not just descriptive and narrative but has been harnessed to create dense, dark and an enigmatic mysterious appearance of forms and images, which is illusive; now present and suddenly absent.

A glance at his oeuvre of past five years reflect compositions that are broadly structured in which the forms are identifiable and colours are privileged, while on the other hand are compositions that are extremely detailed, dense, mysterious, enigmatic, yet containing the images and elements of flora and fauna intricately woven together into a thick tapestry. It is interesting to note that duality that exists in life is clarified poignantly through artistic means and methodologies.

The artistic facility that he has articulated in juxtaposing the dense fine lines to create a sense of delicately defined balanced subtle and heavy chiaroscuro, imparts an aura of mystery, a ploy cleverly used by the artist to draw viewer into the heart of his composition. The lines are amazingly varied in their very fine short strokes, intimately nestling within close proximity to each other and to an extent directional as horizontal, vertical or diagonal. Yet with an eye to balance the positive and negative spaces, Sachin has created here through lines, the balance of energies that exists in the universe as yin and yang, positive and negative or Shiva-Shakti. This is the remarkable dimension of the understanding of his artistry in transcending to the level of abstraction of energy representation.

It is the inherent and well thought out white spaces of his composition that emerge as light, a seminal element that metaphorically describes transcendence and esoteric level. Hence light does not describe his forms materially, rather light manifests as a binding element, gliding and flowing over forms in a languid manner. The suffused inner light, integral to his composition is magical rather than dramatic. Sachin a master craftsman in modulating colours with subtle nuances as yellows, blues and pinks creates light that is unearthly, mysterious and hence enigmatic. The colours predominantly are subtle blue, orange, red cream white, brown and black, which weave intelligently with well thought out lines - an interplay of intense cross hatching makes the works interesting and absorbing. It is not possible to turn away from his work after a glance; rather it beckons for a closer scrutiny, thus establishing a dialogue between his paintings and the viewer.

Further enhancing the aura of ambiguity and mystery are the quasi featureless faces of Shiva and Shakti. Sachin has played with his personalized iconography using symbols and signs that are all pervading in Hindu iconography. There is an insistent articulation with lotus, a flower intimately associated with Lakshmi. The bull with the bells around its neck is ubiquitously pervasive in his artistic exploration as well as the trident and crescent moon of Shiva. Though there is a stereotyped representation in terms of facial features, with blotched black eyes and faces as frontal or in profile, it is the facelessness that creates a greater enigmatic enchantment; marking this ambiguity of presence of absence that defines for Sachin through his artists process the illusion or Maya evident in existence. In decoding this aspect of his style, Sachin has adopted a philosophical approach in deconstructing human nature. The facelessness is also the reflection of artist’s humility, subconsciously declaring to remain away from the glare of the limelight and continue with his art making like a passionate prayer. The narrative of the absence of presence is not only poetic but alluringly beautiful marking the silence as artistic pause. The seen and the unseen, the heard and the unheard, quietitude and chatter are the inherent duality of energies manifesting his compositions.

The varied dimensions of choreographing light, lines, textures and space, which lie at the heart of his works undeniably inscribes the perception of the artist, interpreting his reality and experiences to create the personal narrative of his vision which is as dynamic as it is contemplative. The painterly layers in his compositions are worked to create a sense of palimpsest of time and memory. The metaphor of memory paradoxically continues as its metonym, which involves space and time corresponding to embracing energy that incidentally relates to the concept of ‘roots and identity’ for the artist, as well injecting in the technique of layering a sense of time in the space of the painting, not only the actual time of the complicated making of work, but also an allegorical time of different meanings and suggested memories. The memories I wish to emphasize is seminal in the works of Sachin, as it is certain experiences resolving out of his meditation and the resultant imagery that configures on his paper or the canvas. This process aids in delivering the vision to Sachin for transformation according to his artistic sensibility. The intention of the artist here involves a mental life of private and unknowable to others but it nevertheless deliberates as the service to the artist. The profundity of his abstracts manifests these unknowable making them enigmatic, and hence increasing the sense of power and dynamism.

Hence in appreciating the works, it is in the details rather than in the discerning narrative that attention should be directed. Each line or brush stroke laden with pigment load, the artist’s intentions and a feeling or an emotional state, or an absence at the horizon of the mind comes to the fore and everything is felt in abstraction when seen from a close proximity. Sachin’s works are an immersive experience. As a lover of nature he has travelled extensively and has spent time in the lap of Mother Nature. Always an observant and keenly perceptive artist, he has scrutinized the different aspects of Prakriti which as a creative fecund feminine principle, many elements of flora and fauna emerge as small saplings, leaves, tree, water, moon, bells, rocks, pebbles houses etc. This is Sachin’s observed reality that intuitively marks its presence within his composition. The metaphorical energy of Prakriti that brings alive the dormant dimensions of Purusha are the epicenter of his compositions, which the artist explores with ephemeral imagery, marking the absorption of the viewer to clarify and recognize the forms of Shiva and Shakti. It is this presence of absence that is so magical in his compositions as well as the truth of his imagination. Thus the process involved in identifying the imagery of Shiva-Shakti and natural elements or Prakriti becomes layered bringing out the dimensions of being and non being.

His works invites the viewer to an absorbing journey in his enchanting universe exploring the cosmic connection through flora and fauna, the harmony of colours, and the expanse of mystical landscapes. Sachin's artistic odyssey is a testament to his deep connection with self and tradition, retold through modern perspective, weaving together the colourful threads of mythology, the alluring glory of nature, and the unyielding power of Shakti. It is in the female that he centers the perennial fecund energy. Through layered construction, multiple forms are created, producing an ethereal space from his mythic imagination.

As thinking and an intuitively spontaneous artist, a paradox indeed, the artistic expressions emerges with his thoughts and his forms gestalts to present the viewer different images as perceived by them according to their experiences. From between the layers of his subconscious emerge the concealed images that mark their presence at contingent moment in his artistic process to occupy seminal spaces within his artistic expressions.

DR. ASHRAFI S. BHAGAT

-

Echoes and windows: Kalakriti Art Gallery exhibitions explore repetition and spirituality

in the press, YOURSTORYMadanmohan Rao, YOURSTORY, 10 May 2025 -

Windows to the Gods - A Divine Vision in Art

Hans IndiaAnna Rao Gangavalli, Hans India, 20 April 2025 -

‘Windows to the Gods’ & ‘Echoes Within’: A Celebration of Art at Bikaner House

Daily PrabhatDaily Prabhat, 8 March 2025 -

‘Windows to the Gods’ & ‘Echoes Within’: A Celebration of Art at Bikaner House

NewsnowNewsnow, 8 March 2025 -

'Windows to the Gods' & 'Echoes Within': A Celebration of Art at Bikaner House

LatestlyLatestly, 8 March 2025 -

‘Windows to the Gods’ & ‘Echoes Within’: A Celebration of Art at Bikaner House

Dailyhuntdailyhunt, 8 March 2025 -

'Windows to the Gods' & 'Echoes Within': A Celebration of Art at Bikaner House

HT SyndicationHT Syndication, 8 March 2025 -

‘Windows to the Gods’ & ‘Echoes Within’: A Celebration of Art at Bikaner House – World News Network

WNN | World News NetworkVishu Adhana, WNN | World News Network, 8 March 2025 -

‘Windows to the Gods’ & ‘Echoes Within’: A Celebration of Art at Bikaner House

Take OneTake One, 8 March 2025 -

विंडोज टू द गॉड्स' और 'इकोज़ विदिन': बीकानेर हाउस में कला का उत्सव

जनता से रिश्ताGulabi Jagat, जनता से रिश्ता, 8 March 2025 -

'Windows to the Gods' & 'Echoes Within': A Celebration of Art at Bikaner House

Webindia123Vishu Adhana, Webindia123, 8 March 2025 -

'Windows to the Gods' & 'Echoes Within': A Celebration of Art at Bikaner House

Big News NetworkBig News Network, 8 March 2025 -

‘Windows to the Gods’ & ‘Echoes Within’: A Celebration of Art at Bikaner House

ThePrintThePrint, 8 March 2025 -

'Windows to the Gods' & 'Echoes Within': A Celebration of Art at Bikaner House

ANIVishu Adhana, ANI, 8 March 2025 -

Windows to the Gods – 3rd Edition

GraziaGrazia, 6 March 2025 -

Windows to the Gods

AbirpothiAbirpothi, 5 March 2025 -

Windows to the Gods

Lifestyleasiaindialifestyleasiaindia, 4 March 2025 -

Kalakriti Art Gallery presents “Windows to the Gods – 3rd Edition”

in the press, Travelers Worldin the press, Travelers World , 4 March 2025 -

8 Events You Can't Miss This March In India: Art, Music, Culture, And More

NDTVSushmita Srivastav, NDTV, 1 March 2025